My Father and His Father's Grave

But this is not the story of a life.

It is the story of lives knit together,

overlapping in succession rising

again from grave after grave.

Wendell Berry, from "Rising"

In the last year of my father's life he obsessed about his father's grave. His memory was failing, my stepmother had died unexpectedly, and we had moved him from his home of nearly 50 years to an assisted living facility close to me. His life had been upended in nearly every way, yet regularly he would call the office at St. Patrick's Cemetery in Butte, Montana to assure that his father's grave was being cared for.

Years before, when Daddy last visited the grave, he found it sadly neglected. A group of local Hiberians had begun to clean-up St. Patrick's, considered sacred ground by many in Butte for the number of Irish ancestors buried there. Daddy sent money for the cause, still he was not relieved of what he saw as his duty to honor his father's memory and preserve his grave.

Jerry Egan died of consumption when his son, my father James, was not yet six. Daddy's memories of him were few; I cannot recall him telling a single story about his father. No mementos except his gold watch and a few photographs. In a faded photograph taken at the Annual Convention of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Great Falls, Montana in 1923, he's easy to identify among the dozens of men in the picture, a tall man with a rakish hat standing beside my grandmother, who I remember as unsmiling, looking happy under her elegant hat.

When I place his formal portrait alongside pictures of my father and my lost brother, I see a remarkable resemblance among the generations: three handsome, clear-eyed men.

The most enduring relic of the man is his name engraved on the base of the tall, slender obelisk of black Quincy granite in St. Patrick's cemetery—the RELA memorial:

Jeremiah Egan, Born 1882, Died 1926

The RELA, the Robert Emmet Literary Association, was not a book club. Named for the Irish patriot Robert Emmet, it was the Butte camp of the Clan-na-Gael, an American-based revolutionary group whose was purpose was to fight for Irish independence. Beyond being Butte's version of the Irish Republican Army, the association also served a social and supportive purpose in the lives of its immigrant members, the large majority of whom were miners. Initiation into the RELA, dependent on the recommendation of two current members in good standing, brought a measure of respect in the community, improved the prospect of safe and steady work, and in the event of disability or death, a degree of financial support for the family.

Injury, illness, and early death were accepted hazards of hard rock mining. Membership in the Emmets, as the RELA members were called, assured that widows and orphans were supported. An honorable burial in RELA plot with the member's name engraved on the memorial helped financially and emotionally.

As a child, my father could not have understood much of his father's relationship to the RELA and his revolutionary beliefs. In his later years, he learned as much as he could. In a box of Daddy's memorabilia, I discovered multiple manila folders marked in his bold penmanship where he had tracked down the manifest of Jerry Egan's passage to America where he was being sponsored by his cousin on his mother's side, Michael Browne, the record of his first lodgings at The Florence Hotel in Butte, a copy of his marriage license to Mary Sullivan, and documentation of his involvement with the Emmets, including the member number, 285, that he used to protect his identity. A photocopy of meeting notes in his father's own fine handwriting, taken when he was the RELA recording secretary, show Jerry Egan, patriot, in action.

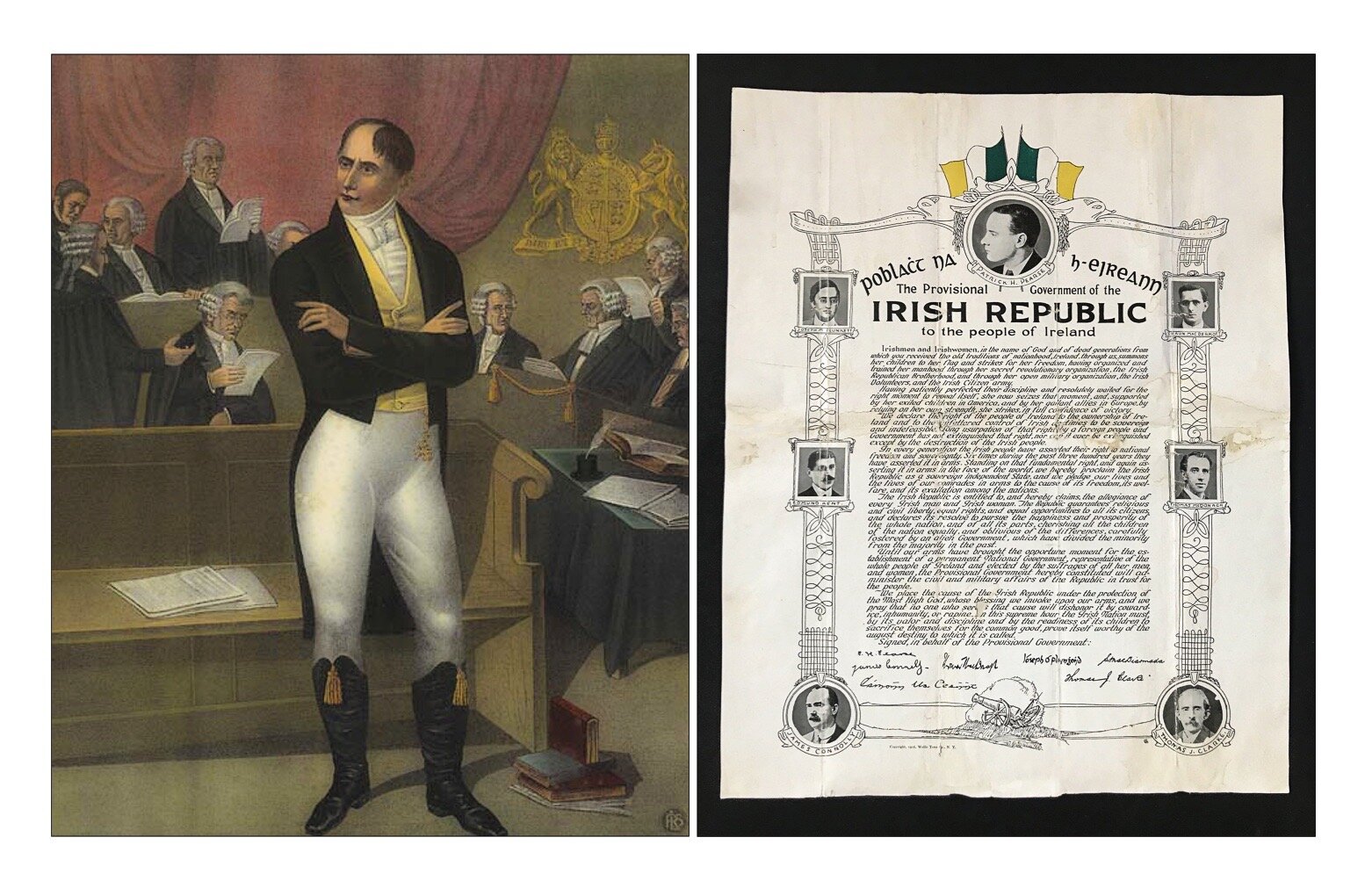

Growing up my father was always good for a song, usually an Irish revolutionary ballad sung his clear tenor. He never needed St Patrick's Day or a drink to give us a rendition of "Danny Boy." When my grandmother died forty years after her husband, among the few things Daddy took from his childhood home were a print of the "Trial of Robert Emmet" and a copy of the Proclamation of Irish Independence.

What compelled Daddy's continual calls to the St. Patrick's cemetery, I don't truly know. What I do know is that he took seriously the admonishment of the Corporal Works of Mercy—to bury the dead. I was with him the day he purchased a plot at Ivy Lawn Cemetery in Ventura, California in 1968. My younger brother, Jimmy, aged 16, had been killed in an accident and we needed to bury him.

That day he bought a "family" plot with four contiguous graves: one for my brother, one for his best friend Eric, who had been driving the van when they were hit by the northbound Southern Pacific at La Conchita, and the remaining two for the eventual burials of my mother and himself.

He visited the graves often bringing flowers for both Jimmy and Eric. My mother, who never recovered from Jimmy's death, died seven years after my brother and was laid to rest next to her favorite child. Daddy increased the number of bouquets, and brought my sister and me along with him whenever he could.

When Daddy's younger and only brother, Eddy, dropped dead of a heart attack several years later, he brought him back from the east coast and buried him in his place in the plot. My uncle's death was a chilling reminder of how short a time we might have. He whispered his intention to marry Frances, his girlfriend of several years, to me during Eddy's funeral. More flowers, more visits.

With no more room in the original plot and a heightened awareness of the inevitable need for a grave, my father determined to purchase another "family" plot. This one would have a place for Daddy and Frances plus two. When he called to ask if I wanted one of the graves, I didn't know how to respond, but I knew I couldn't say no.

To this day, I justify my acquiescence by thinking of my space in the plot as a piece of California real estate, nicely landscaped.

When I visit the graves, I stop at the small flower stand next to the cemetery and buy bouquets for them all: Daddy, Frances, Mommy, Jimmy and Eddy. If the site isn't trimmed or the headstones stained, I call the office at Ivy Lawn to make sure maintenance takes care of the problem. After all Daddy purchased perpetual care. Rain was falling the last time I arranged the flowers—on a March 23, the anniversary of my brother's death.

While I think I think of them all often, the ritual of honoring them takes on poignancy as I age. I return to Ivy Lawn again and again, not out of duty. I return to remember, to honor the memory of their lives, and to secure my own place in an enduring human story of love and loss.